When his parents separated, he spent part of his young life with his mother in Geneva and part with his father in the Soviet Union. His adventure with writing began while he was studying in Moscow, when he started creating short stories. One of his first novellas, “In the City of Berdyczow,” received a very favorable response and positive reviews of his work were expressed by Maxim Gorky and Mikhail Bulgakov. The novella was filmed after Vasily’s death in 1967, but due to censorship it did not appear until 20 years later.

When war broke out between the Third Reich and the Soviet Union, his mother was murdered with the other Jews in Berdychev. Vasily was deemed unfit for military service, so he volunteered for the Red Army’s propaganda newspaper titled. “Krasna Zwiezda” (Red Star) as a war correspondent. He described the major battles on the front, including those at Moscow, Stalingrad, the Kursk Arch and the Battle of Berlin. He wrote battlefield reports, but his stories also appeared in the press. In 1944 he wrote a report “Hell of Treblinka” from his impressions after discovering the concentration camp there in 1943. He also enriched the reportage with interviews with prisoners of that camp. It is one of the first eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust. The report was later used during the Nuremberg trial by prosecutors. Vasily wrote thus:

(…) it might have seemed that there was nothing more terrible in the world. But those who were in Camp No. 1 knew well that there was something more terrible, a hundred times more terrible, than their camp. In May 1942, the Germans began construction of a new camp, located 3 kilometers from the labor camp. (…) In this camp, nothing was adapted for life, everything was adapted for death.

Treblinka consisted of two camps. Camp 1 was a labor camp, while Camp 2 became the site for the extermination of Jews from Poland, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Yugoslavia, Germany, as well as Roma and Sinti. The camp began operating in July 1942, while the last transport arrived in August 1943. The Nazis demolished the camp in an attempt to erase the traces of their murderous activities. The area was plowed and sown with lupine. When the Red Army entered the area in the summer of 1944, there was no trace of the camp’s buildings, but human remains were found in the ground. Vasily wrote:

We arrived at the Treblinka camp in early September (…). It was quiet. The crowns of the pine trees, growing along the railroad track, barely swayed. On these very pines, on this sand, on this old trunk looked millions of human eyes from the wagons approaching slowly to the platform. Silently the ash creaks underfoot, shredded cinders on the black road (…) we enter the camp, step on the soil of Treblinka. Lupine pods burst from the lightest touch, burst with a crackle, millions of grains fall on the road. The sound of falling grains, the crackle of bursting pods merge into one quiet and sad melody (…)And the ground sways underfoot, plump, greasy, as if lavishly doused with linseed oil, the bottomless ground of Treblinka, shaky as the abyss of the sea (…) throws out crushed bones, teeth, things, papers – it does not want to hide the secret.

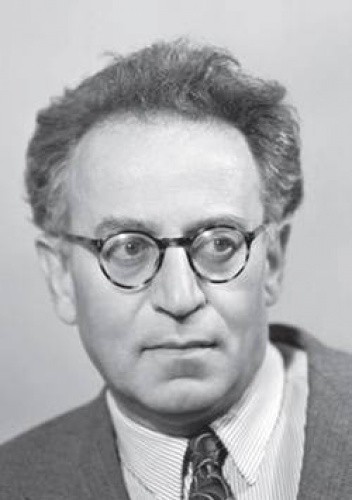

Vasily in the 1950s began to criticize the communist system, and his works were censored. He died in oblivion, in poverty and illness. He was rehabilitated along with his work at the end of the Soviet Union.